The Hundred Years War 1337 -1453

| Site: | Plateforme pédagogique de l'Université Sétif2 |

| Cours: | Ktir-K: Studying Civilization Texts 3rd Y |

| Livre: | The Hundred Years War 1337 -1453 |

| Imprimé par: | Visiteur anonyme |

| Date: | vendredi 3 octobre 2025, 21:29 |

1. The Root Causes of the War

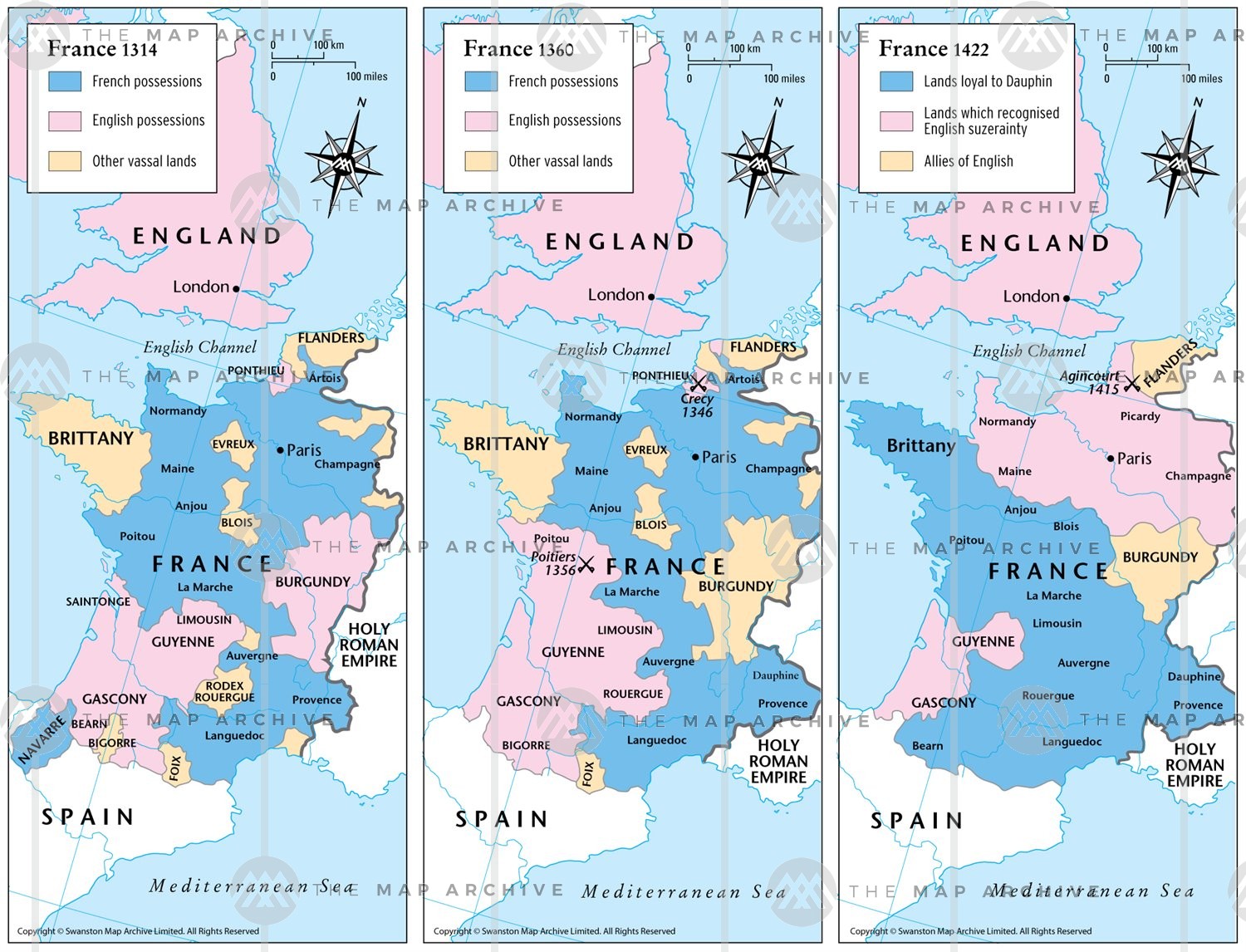

The Hundred Years War was the name given by historians to a series of battles between England and France about English lands in Northwest France, the war as a matter of a fact lasted more than a century and affected the whole European continent. To understand the tensions between the English and French thrones over continental land, we should go back to 1066 when William of Normandy conquered England that we have discussed in the second lecture. In the third lecture, we explored how his grandson Henry II had gained further lands in France, by inheriting the County of Anjou from his father and ruling the Dukedom of Aquitaine through his wife. Tensions grew even more between the kings of France and English Vassals. In lecture four, we saw how King John of England lost Normandy, Anjou, and other lands in France in 1204, and his son was forced to sign the Treaty of Paris ceding this land. He kept Aquitaine and other territories to be held as a vassal of France. according to Robert Wide " "This was one king bowing to another, and there were further wars in 1294 and 1324 when Aquitaine was confiscated by France and won back by the English crown. As the profits from Aquitaine alone rivalled those of England, the region was important and retained many differences from the rest of France" (p 13).

In 1337, King Philip of France seized the Duchy of Aquitaine while King Edward III of England was at war with David Bruce of Scotland. According to many historians, this was considered to be the direct cause of the Hundred Years War, especially that Edward III claimed to be the righteous Heir of the French throne and named himself King of France. His claim was based on the fact that he was the direct heir, from his mother's side, of the French throne after the childless King Charles IV died. Edward was 13 at that time so the French Assembly elected Philip de Valois to be King. France was already fractioned from the inside between the King's men and major nobles about ports and lands. This Fraction weakened the kingdom and made it easy for Edward to infiltrate it.

2. English Victories

Edward III’s strategy to attack France was divided into two parts. First, He got closer to the French nobles who were in disagreements with Philip in order to make new allies. Then, He led armed raids on France to demolish the lands and cause the Valois king economic loses as a result they would terrorize the French.

These invasions were historically known as chevauchées. As a reaction to the English acts, the French invasions on the British coast were unsuccessful and the English victoriously won at Sluys. England won two famous battles at Crecy (1346) and Poitiers (1356), in the second battle they captured the Valois French King John. The English military victories gave them an upper hand on the French who felt helpless. After Edward III death his son “the black Prince” continued his father’s path.

Kingless France was collapsing, with large parts in rebellion and the rest beset by mercenary armies, Edward wanted to take control of Paris and Rheims, where royal coronation takes place. He took neither but obliged the "Dauphin"—the name for the French heir to the throne - to sing the Treaty of Brétigny in 1360 to drop his claim to the throne. Edward won a large and independent Aquitaine in addition to other lands and money “but” according to Wide “complications in the text of this agreement allowed both sides to renew their claims later on”.

3. The French Resistance

England and France fought each other for the Castilian crown. The long war caused Britain more debts so they imposed more taxes on the people in Aquitaine since based on the Magna Carta the king can no longer impose new taxes or raise the old ones in England. Consequently, Aquitaine’s nobles left to France who seized back the lands and war erupted once more in 1369. The new Valois King of France, Charles V, helped by Bertrand du Guesclin, a guerrilla leader, reconquered much of the English gains while avoiding any large pitch battles with the attacking English forces. The British were better armored especially that they could develop the longbow a strategic weapon which could shoot several arrows at the same time and for a longer distance.

The Black Prince died in 1376, and Edward III in 1377, both sides were avoiding encounters. By 1380, the year both Charles V and du Guesclin died so both sides were growing tired of the conflict. England and France were both ruled by minors, according to Wide when Richard II of England came of age he “reasserted himself over pro-war nobles (and a pro-war nation), suing for peace. Charles VI and his advisors also sought peace, and some went on crusade. Richard then became too tyrannical for his subjects and was deposed, while Charles went insane”. At that period the bubonic plague first struck Europe from 1346 to 1351. It returned in waves that occurred about every decade into the 15th century, leaving major changes in its wake. Some historians estimate that 24 million Europeans died of the plague—about a third of the entire population. The rate of deaths sped up leading to changes in Europe's economic and social structure and consequently led to the decline of feudalism. Trade and commerce reduced during the plague years.

As Europe began to recover, the economy needed to be rebuilt. But it wouldn't be rebuilt in the same way, as feudal lords lost their powers and money. After the plague, historians accentuated the shift in power from nobles to the common people. A huge number of workers died and those who survived could, thus, demand more money and more rights. In addition, according to Wide “many peasants and some serfs abandoned feudal manors and moved to towns and cities, seeking better opportunities. This led to a weakening of the manor system and a loss of power for feudal lords”. After the plague, a number of peasant rebellions broke out. When nobles tried to return to the system from before the plague, peasants revolted throughout Europe in France, Flanders, England, Germany, Spain, and Italy. The most famous of these revolts, according to historians, was the English Peasants' War in 1381. The English rebels went to London and presented their demands to the king, Richard II who ordered to kill the leader of the rebellion and weakened the revolt. Still, in most of Europe, the time was coming when servitude would end.

4. Henry V Changing the Balance

In the 15th century, France was divided between two major noble houses — Burgundy and Orléans — over who is going to rule on behalf of the mad king. This period was known as the French civil war in 1407 after the head of Orléans was murdered; the Orléans side became known as the "Armagnacs" after their new leader. Danide explained that “after a misstep where a treaty was signed between the rebels and England, only for peace to break out in France when the English attacked”. Henry V ascended the throne of Britain in 1415. His first move led to the historically renowned battle: Agincourt. Henry was heading to Calais when he faced a larger French army that outnumbered the men with him. Henry’s men were paid knights wearing light clothes and armed with their famous longbows, these men fought for their land alongside their king. The French army, on the other hand, constituted of noble lords in shiny armors on horsebacks who fight for chivalry. These were the main reasons that led to Henry’s flawless victory that gave a boost to his reputation and allowed him to raise further funds for the war and made him a legend in British history. Henry returned again to France, to seize lands instead of carrying out chevauchées; he soon had Normandy back under control. The French king decided the same as the English and started recruiting his army from commoners and paying them with money collected by taxes in order to have stronger forces.

5. An English King for France

Conflicts between the houses of Burgundy and Orléans continued. This time John, Duke of Burgundy, was assassinated by one of the Dauphin’s party. As a reaction to that, his heir allied with Henry, coming to terms in the Treaty of Troyes in 1420.

Henry V of England married daughter of the Valois King so automatically he became his heir. In return, England would continue the war against Orléans and their allies, which included the Dauphin. Decades later, in Wide’s records, a monk said: “This is the hole through which the English entered France”; when he was observing the skull of Duke John. The Treaty allowed the English and Burgundian to seize largely the north of France while the south was still under the control of the Valois heir to France and the Orléans faction. In August 1422, Henry died and shortly after the mad French King Charles VI followed. Consequently, Henry’s nine-month-old son became king of both England and France with north France acknowledgement.

6. Joan of Arc and the End of the War

Although the relationship between Henry VI and the Burgundians became restless, the attacks on Orleans continued and by September 1428 they were besieging it. At that time people were losing hope and felt week compared to the English which lessened their confidence. At the age of 13, Joan of Arc a peasant girl from the countryside of Orleans claimed to have heard heavenly voices instructing her to liberate Orleans, help the Dauphin Charles to be crowned as king and drive the English out of France “Her impact revitalized the moribund opposition, and they broke the siege around Orléans, defeated the English several times and were able to crown the Dauphin in Rheims cathedral” (Wide 2017). Joan resurrected hope in people drove them to victory, but wanted to fulfil the last mission by attacking Paris without the permission of the king who was trying to make peace with the lord of Burgundy. She was captured by the English and accused her of heresy; the church executed her by burning her on the stake, alive.

After a few years of stalemate, “they rallied around the new king when the Duke of Burgundy broke with the English in 1435. After the Congress of Arras, they recognized Charles VII as king. Many believe the Duke had decided England could never truly win France” (Wide 2017). The unification of Orléans and Burgundy under the Valois crown weakened the English side who continued the war against all odds. The fighting was paused temporarily in 1444 with an armistice and a marriage between Henry VI of England and a French princess. The English surrendered Maine to achieve the truce which caused an uproar in England.

War soon began again when the English broke the truce. Charles VII made reforms the French army, and this new model made great advances against English lands on the continent. The French won the Battle of Formigny in 1450, took back Calais from the English by the end of 1453, and killed English commander John Talbot at the Battle of Castillon. With the French taking the upper hand, they victoriously won the war and it was successfully over.

7. The Impact of the War on Europe

According to Wide:

The Hundred Years’ War contributed to the decline of feudalism by helping to shift power from feudal lords to monarchs and to common people.

During the struggle, monarchs on both sides had collected taxes and raised large professional armies. As a result, kings no longer relied as much on nobles to supply knights for the army.

In addition, changes in military technology made the nobles’ knights and castles less useful. The longbow proved to be an effective weapon against mounted knights. Castles also became less important as armies learned to use gunpowder to shoot iron balls from cannons and blast holes in castle walls.

The new feeling of nationalism also shifted power away from lords. Previously, many English and French peasants felt more loyalty to their local lords than to their monarch. The war created a new sense of national unity and patriotism on both sides

In both France and England, commoners and peasants bore the heaviest burden of the war. They were forced to fight and to pay higher and more frequent taxes. Those who survived the war, however, were needed as soldiers and workers. For this reason, the common people emerged from the conflict with greater influence and power.

In this lesson you learned about the decline of feudalism in Europe in the 12th to 15th centuries. The major

causes of this decline included political changes in England, disease, and wars.

Cultural Interaction: The culture of feudalism, which centered on noble knights and castles, declined in this period. The spread of new military technologies such as the longbow and cannon made the armored knight and fortified castle less important.

The disaster of the plague influenced culture, causing some to celebrate life in the face of mass death. Others had the opposite reaction and fixated on death and the afterlife, which was reflected in art.

Political Structures: In England the signing of Magna Carta and other political reforms laid the foundations for more democratic forms of government.

The Hundred Years’ War between France and England shifted power away from feudal lords to both the monarchy and the common people. It also increased feelings of nationalism, as people began to identify more with the king than with their local lord.

Economic Structures: The feudal system of agriculture and land ownership declined in this period. The plague caused trade and commerce to slow. Due to the death of one third of the population of Europe from the plague, labor shortages occurred. This created greater economic opportunities for peasants, and they demanded increased wages.

Social Structures: The hierarchical social structure of feudalism was destabilized as a result of the plague, which affected all social classes equally. When the plague passed and feudal lords attempted to reestablish their authority, peasant rebellions occurred as commoners refused to accept the old social order. The common people also gained greater power as a result of the Hundred Years’ War.

Human-Environment Interaction: The bubonic plague spread over trade routes from Asia to western Europe and killed one third of the population of Europe. Its spread was aided by the fact that most people lived in unhygienic conditions at this time, especially in the cities. In the wake of the plague many peasants left their manors for greater opportunities in the cities